Deceleration of Economic Growth

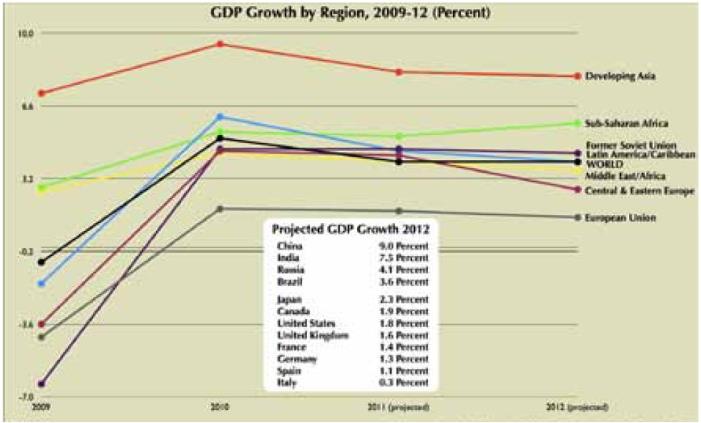

On 20 September 2011, the International Monetary Fund released its latest economic growth projections. The IMF forecast is sobering, anticipating a slowdown in all regions of the world economy (EXHIBIT 1).

EXHIBIT 1

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, September 2011

The economic deceleration is particularly marked in Japan (where GDP growth is expected to fall from 4.0 percent in 2010 to –0.5 percent in 2011) and the United States (3.0 percent to 1.5 percent). Germany, whose export manufacturing sector propelled that country’s rebound from the Great Recession in 2009-10, faces a decline in growth to 2.7 percent in 2011. Anticipated growth rates in other developed economies are even weaker: 2.1 percent in Canada, 1.7 percent in France, 1.1 percent in the United Kingdom, 0.8 percent in Spain and 0.6 percent in Italy.

The IMF forecasts a modest increase in GDP growth in the U.S. in 2012 (1.8 percent) and U.K. (1.6 percent). Japan is expected to grow by 2.3 percent next year as the effects of the March 2011 earthquake/tsunami dissipate. But growth in the Euro zone is projected to slow to 1.1 percent in the coming year, reflecting the contagion effects of financial troubles in Greece, Italy and other heavily indebted countries.

High-growth emerging markets are not immune from the global economic slowdown. From 10.3 percent in 2010, China’s GDP growth is forecast to fall to 9.5 percent in 2011 and 9.0 percent in 2012. India and Brazil also face falling growth rates in 2012 (7.5 and 3.6 percent). Turkey, which posted Europe’s highest growth rate in 2010 (8.9 percent), is projected to slow to 2.2 percent in 2012. An exception to the emerging market slowdown is the Russian Federation, whose GDP growth has held steady since the global financial crisis amid strong oil and gas prices.

Headwinds in the Global Economy

The IMF’s September report offers a considerably more pessimistic assessment than that of the Fund’s previous World Economic Outlook in June 2011, illustrating the worsening of global economic conditions during the summer.

The ebbing of the world economic recovery reflects the supply side shocks resulting from the natural disaster in Japan (which disrupted the supply chains of the automotive and electronic industries) and rising commodity prices (which surged to pre-recession levels amid rising demand by China and other resource intensive emerging markets).

But the primary factor slowing the world economy is the looming financial crisis in the advanced industrialized countries. Unsustainable debt levels are forcing Western governments to shift from fiscal stimulus (applied in 2009-10 to spur short-term recovery from the crisis) to fiscal consolidation (now deemed essential for long-term macroeconomic stability). As the effects of the fiscal stimulus programmes fade, policymakers look to the private sector for the demand side response needed to sustain economic recovery. But the private sector has not filled the void left by the withdrawal of government spending, as heavily indebted Western consumers deleverage and banks withhold credit amid persistent uncertainties about global financial stability.

Unable to strike an effective balance between fiscal consolidation and economic growth, Western countries now face a heightened risk of the double dip recession that most analysts had discounted as improbable in late 2010.

Fiscal Consolidation in the U.S.

The August 5 downgrade of U.S. debt by Standard and Poor’s – the first sovereign downgrade in American history – symbolised the erosion of America’s global financial standing in the wake of the dispute between the Obama Administration and Congressional Republicans over the federal government’s debt ceiling.

But the S & P action (and threatened downgrades by Fitch and Moody’s) had little immediate effect on the international financial metrics of the United States. Indeed, the U.S. dollar appreciated against major currencies (Euro, Pound Sterling, Swiss Franc, Canadian Dollar, Australian dollar) during the six weeks following the August 5 downgrade. During the same period, yields on U.S. Treasuries declined, reaching a record low on September 21.

The financial market’s non-plussed reaction to the S & P downgrade demonstrates the unique position of the United States, which as the world’s largest economy and holder of the main international reserve asset enjoys certain prerogatives unavailable to smaller countries. The dollar’s recent rise also reflects mounting anxieties about financial stability in Europe, where fiscal conditions are even graver than in the U.S.

But while the unprecedented downgrading of American debt has not precipitated a flight out of dollar assets, the episode does underscore the political dilemmas of fiscal consolidation in the United States. While issuing warnings about U.S. sovereign debt, the rating agencies emphasised their concerns over Washington’s ability to surmount the political impasse between the Republican Party (ideologically opposed to tax increases) and the Democratic Party (resistant to the entitlement reforms necessary to achieve long-term fiscal stability).

Financial Turmoil in the European Union

Europe’s financial troubles quickly escalated in summer/autumn 2011. On June 15, the EFSF (European Financial Stability Facility, established in May 2010 as the European counterpart to the American Troubled Asset Relief Programme) issued a €78 billion package to Portugal. On July 21, the leaders of the 17 Euro zone countries agreed to draw €109 billion from EFSF’s €440 billion facility as a low-cost loan to Greece. Supplementing the EFSF loan, the Euro countries negotiated a €37 billion Greek debt exchange agreement with banks and insurance companies.

This aid programme (which follows Greece’s first bailout of €110 billion in May 2010) requires ratification by Euro zone governments. By late September, only five member states (Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg and Spain) had ratified the Greek package. Financially stable Euro countries voiced skepticism about the deal. Finland demanded cash collateral, while Slovakia deferred a parliamentary vote until December.

On 21 September, the beleaguered Greek government announced a further set of austerity measures to secure release of the next bailout tranche of €8 billion, including deep pension cuts, a reduction of the tax threshold for low income households, and a partial pay scheme for 30,000 public sector employees. Predictably, this announcement triggered an outraged response by Greek trade unions. Transit workers staged a 24 hour strike, while the Greek Civil Servants’ Confederation (ADEDY) proclaimed a three day work stoppage in the greater Athens area. With riots in the streets and mounting pressure by the opposition New Democracy party, it is unclear whether the Greek government possesses the political capacity to inflict further austerity on a populace already pushed to the brink.

Economic growth (a more politically palatable remedy to Greek’s financial woes than austerity) also appears out of reach of Greek policymakers. Greece’s membership in the common currency area prohibits use of the exchange rate as an export promotion tool. The alternative path–exiting the Euro zone and returning to a sharply devalued drachma to stimulate Greek exports – has no precedent in the EU and is resisted by Germany and other countries that seek to maintain the integrity of the Economic and Monetary Union.

Here the recent experience of Ireland is instructive. Like Greece, Ireland is a small, open European economy whose financial crisis prompted an externally imposed austerity programme. Draconian cost-cutting instigated an “internal devaluation” in Ireland, strengthening the country’s export competitiveness and laying the foundation for an economic rebound. Furthermore, Ireland’s high-technology manufacturing sector renders it better positioned for export-led growth than Greece, whose export sector relies heavily on shipping and tourism.

With its policy options narrowing, Greece faces a high likelihood of a default by early 2012. In an optimistic scenario, the country will undergo an “orderly default” whose contagion effects would be largely contained. In a pessimistic scenario, a Greek default would inflict serious damage on major European banks holding the country’s sovereign debt, precipitating a global credit squeeze comparable to the crisis following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008.

Debt Management in the Advanced Industrialised Countries

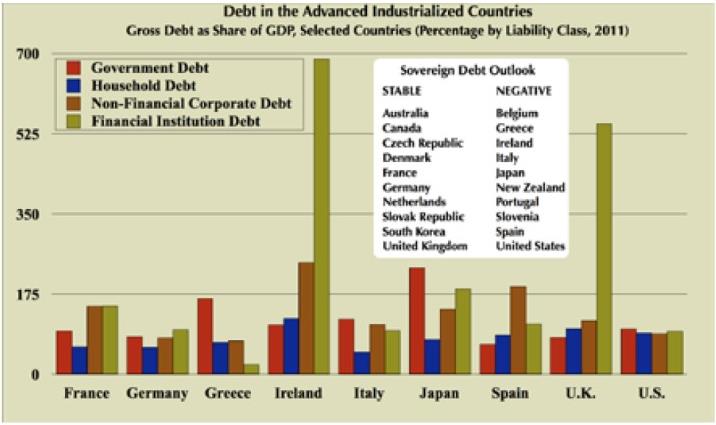

Greece is an unusual case insofar as the country’s distinctive political economy– a toxic combination of an outsized public sector and a culture of tax evasion – produced a large sovereign debt that was absorbed by foreign banks amid the financial excesses of the pre-recession years. But Greece is not alone among developed economies groaning under the weight of a debt overhang that will unavoidably restrict Western growth prospects in coming years.

EXHIBIT 2 shows the breakdown of debt by liability class in selected developed economies. The differences between these countries are illuminating. The United Kingdom and Ireland are outliers in financial sector debt (547 and 689 percent of GDP respectively). Japan holds by far the greatest GDP share of public debt (233 percent), surpassing even EU countries with overgrown public sectors (Italy 121 percent, Greece 166 percent). Non-financial corporate debt is heaviest in Ireland (245 percent), Spain (192 percent), and France (150 percent). Household debt shares are not particularly large in the European Union, with the exceptions of U.K. (101 percent) and Ireland (123 percent). Germany stands as the most financially conservative of the advanced industrialised countries, with manageable debt loads in all four liability classes.

EXHIBIT 2

Source: International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report, September 2011

Public/private indebtedness in the United States has not yet reached the alarming levels of some European countries. The size and liquidity of the American capital market, together with the dollar’s role as the principal international reserve asset, better enable the U.S. to finance its deficit than other developed economies.

Furthermore, the U.S. is not hamstrung by an EU-style common currency area, widening the range of economic stimulus policies. But two factors sound alarms about debt management in the United States: (1) the rapid expansion of American indebtedness over the past decade, which has raised absolute and relative levels of public/private debt to unprecedented heights, and (2) the political impasse in Washington that frustrates achievement of what the IMF calls “growth-friendly fiscal consolidation”.

Conclusion: Emerging Markets as Growth Drivers

Even with effective debt management policies, the developed economies are likely condemned to modest GDP growth for years to come. By contrast, many emerging markets are poised for robust economic growth that will strengthen their standing as rising global powers. Emerging market based sovereign wealth funds acted as global liquidity buffers during the post-Lehman credit crunch. The BRIC countries are already major holders of U.S. debt, and China and Russia are currently negotiating Euro bond purchases to ease financial strains in the EU.

But it remains unclear whether the emerging markets can serve as drivers of global recovery, comparable to the “economic locomotive” role the U.S. played during much of the postwar period. To absorb increased exports from growth-starved Western countries, the emerging markets (including but not limited to the BRICs) must undergo a rebalancing from external to internal demand. Under the most optimistic assumptions, such a rebalancing will be a gradual process that will take years. In the meantime, the world economy is likely to develop along two tracks: Strong growth in emerging markets; tepid growth (and perhaps prolonged stagnation) in developed economies.

David Bartlett, Economic Consultant